Oei Hong Djien & the Fake Painting Controversy: TEMPO Article

(English Version)

In April 2012, a prominent Indonesian art collector well known in the Indonesian art world, Oei Hong Djien—commonly referred to as OHD—held an exhibition titled “Back to Basic” at his private museum, the Oei Hong Djien Museum of Fine Art in Magelang, Central Java.

The exhibition showcased various works from his personal collection, particularly Modern Indonesian Art by major artists such as Hendra Gunawan, S. Sudjojono, Soedibio, and others. The opening night was lively, drawing many attendees, including several family members of the featured artists such as the families of Soedibio, Hendra Gunawan, and representatives of the S. Sudjojono family.

However, what began as a festive occasion gradually turned awkward when one of the wives of the featured artists began to express doubts about the authenticity of a painting on display. Soon after, several of the attending artist colleagues, art observers, and critics began to share similar doubts about some of the artworks. One of the skeptics was Saitem, the wife of the late Soedibio. The piece that raised her concern was a painting by her husband titled “Wahyu”, which bore the date 1981—suggesting that it was painted in that year.

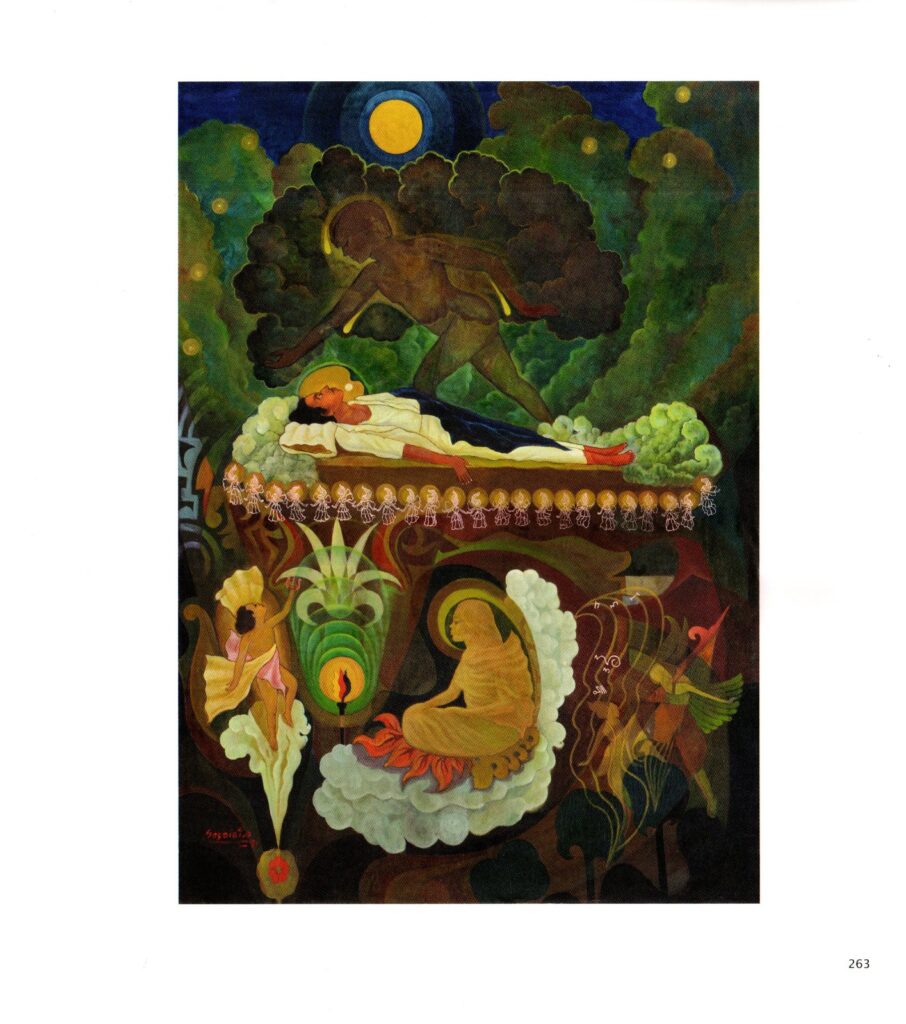

Soedibio’s Painting, Wahyu (1981)

Source: OHD’s Book – Five Masters of Modern Indonesian Art

Saitem was quite shocked when she first saw the painting, because, according to her, by 1981 her husband was already ill and eventually passed away in December of that year. The painting was also very large in size, making it highly unlikely, in her view, that her husband would have been physically capable of completing such a large piece. According to Saitem, who was interviewed by Tempo at the time, her husband only completed five works that year: Semar, Dewi Sri, Gunungan, Ramayana, and finally Menuju Nirwana (“Towards Nirvana”). All of these paintings, she said, were commissioned by an art collector named Harmonie Jaffar, a devoted admirer of Soedibio’s work.

In addition to Saitem, several other members of artists’ families also questioned the authenticity of the works displayed. Among them were Tedjabayu, a relative from the first wife of the late S. Sudjojono, as well as Rose Pandanwangi, his second wife.

Tedjabayu Sudjojono questioned the authenticity of one of his late father’s paintings displayed at the OHD Museum. The painting, titled Pangeran Diponegoro, appeared odd and seemed to be painted carelessly. According to him, it was highly unlikely for the bayonet depicted in the painting to resemble those used during World War II, suggesting a significant historical inaccuracy inconsistent with the era of Prince Diponegoro.

Tedjabayu recalled that his father, S. Sudjojono, always worked based on thorough research and would never paint carelessly. He recounted a time when his father painted his mother, Mia Bustam, in the Prambanan area with an electric pole in the background. To accurately capture the details of the pole, his father willingly made multiple trips to Prambanan, showing just how committed he was to authenticity and precision in his work.

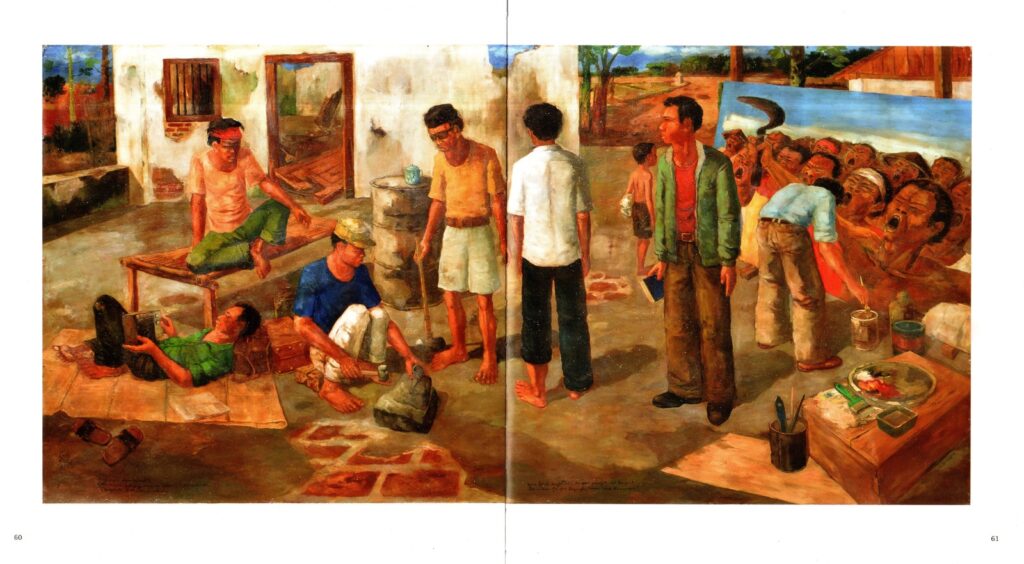

Likewise, Watugunung, the third son of S. Sudjojono from his first wife Mia Bustam, found it very odd when he saw his late father’s painting titled Perjuangan Belum Selesai (The Struggle Is Not Over), dated 1967. According to him, during that year, his father was still deeply traumatized by the mass killings of members of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), and it would have been unthinkable for him to depict a figure brandishing a sickle. That period was one of silence for S. Sudjojono. Aminudin T.H. Siregar supported Watugunung’s observation and argued that the painting was very likely a forgery.

He was convinced because the painting bore the inscription “Djokdjakarta, di sebuah rumah di Bantul” (Yogyakarta, in a house in Bantul). Echoing the sentiments of Watugunung and Aminudin T.H. Siregar, Rose Pandanwangi—Sudjojono’s second wife—also remarked, “After the G-30-S incident, Sudjojono kept a low profile in Jakarta, not in Yogyakarta.”

S. Sudjojono’s Painting, Perdjuangan Belum Selesai (1967)

Source: OHD’s Book – Five Masters of Modern Indonesian Art

Responding to the doubts, Oei Hong Djien simply remarked, “Perhaps Sudjojono was just feeling nostalgic.” Oei was strongly convinced that the work was genuine solely because he had asked his trusted friend, a painter from Temanggung named Kwee Ing Tjiong, who was also a former student of S. Sudjojono.

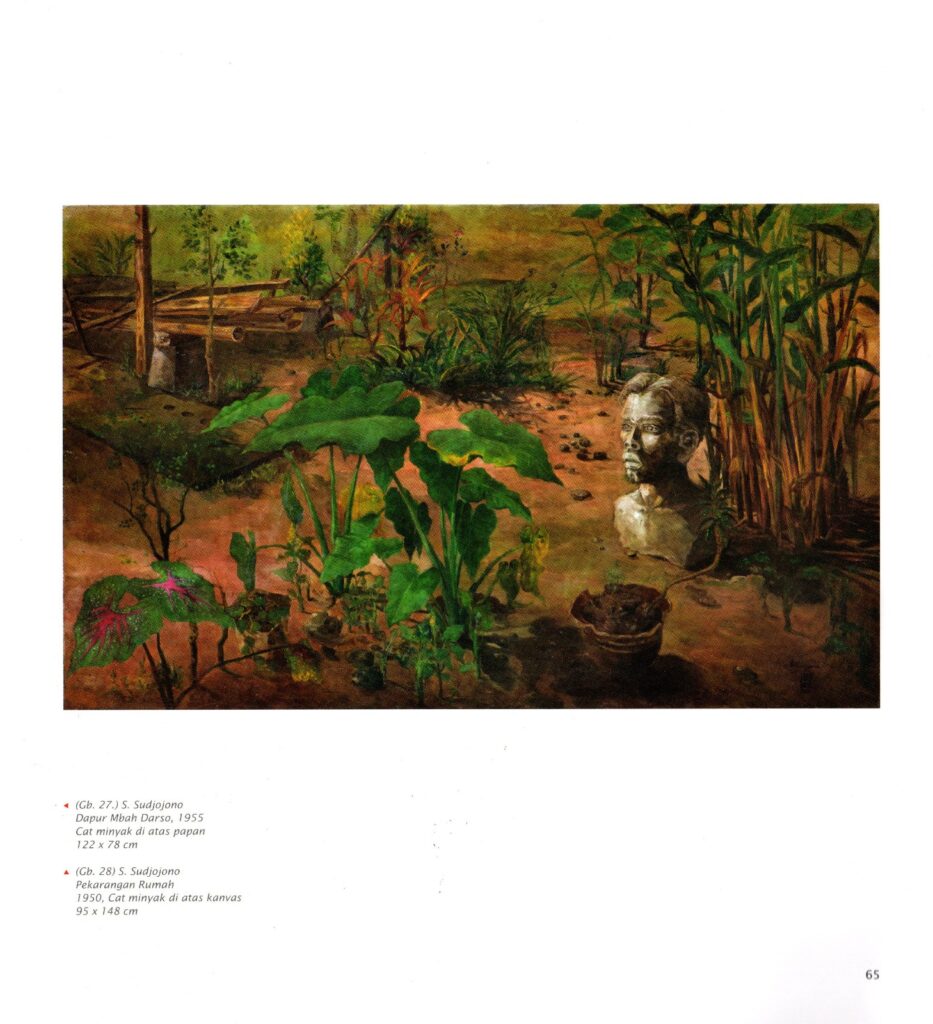

When contacted by Tempo magazine, Kwee Ing Tjiong merely responded that he did not know whether the painting was a forgery. His wife explained that Kwee was unwell, apologized, and asked for understanding regarding his condition—he didn’t want to make any incorrect statements about the artwork. Oei also faced criticism for arbitrarily assigning titles to untitled works. In an interview with Tempo, he admitted to giving the title Pekarangan Rumah (“House Yard”) to a painting by S. Sudjojono, which depicted a yard with taro leaves, bamboo trees, and a stone bust sculpture of a man. Tedjabayu responded that his family’s yard looked nothing like the one depicted, and Aminudin T.H. Siregar argued that the work was clearly a forgery. He suspected the painting was derived from another artwork by the late S. Sudjojono titled In a Village, created in 1950.

Oei was also criticized for arbitrarily giving titles to paintings that originally had none. In an interview with Tempo, he admitted to titling a S. Sudjojono painting as “Pekarangan Rumah” (House Yard), which depicted a yard filled with taro leaves and bamboo trees, along with a stone statue shaped like a male head and torso. However, Tedjabayu responded that the family’s actual house yard did not resemble the scene in the painting. Meanwhile, Aminudin T.H. Siregar stated that the painting was definitely fake and suspected that it was copied from another S. Sudjojono painting titled “In a Village” created in 1950.

Painting by S. Sudjojono, Pekarangan Rumah (1950)

Source: OHD Book: Lima Maestro Seni Rupa Modern Indonesia

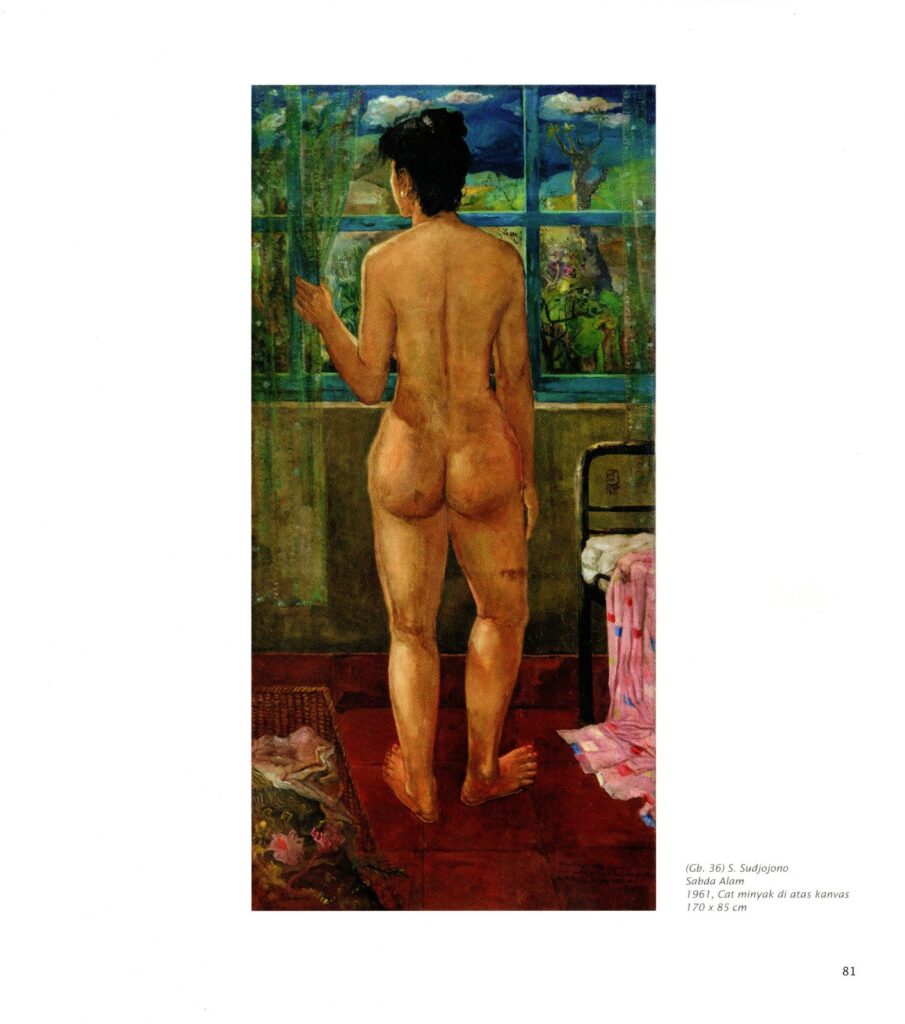

In another interview with Tempo magazine, Mrs. Rose Pandanwangi recounted an incident when Ing Tjiong showed her a painting through a catalog and asked, “Is this you, Mrs. Rose?” Upon seeing the painting, Rose only showed a surprised and confused expression because she felt that the figure in the painting was not her. She then replied, “I don’t think so, Tjiong.”

The painting was titled Sabda Alam (1961). Mrs. Rose revealed in the interview that she was never painted in such a pose. After seeing the painting, she refused to enter the museum because she feared being questioned by reporters, as the figure in the painting did not resemble her.

A few days later, Mrs. Rose saw the same painting again in the book published by Oei Hong Djin titled Lima Maestro Seni Rupa Modern Indonesia. The book included the following description of the painting: “Nude paintings by Sudjojono do not merely depict physical nakedness but contain elements of romance and poetry. Sabda Alam (1961, Fig. 36) portrays a young Rose just after waking up, standing naked behind a glass window, drawing back a transparent curtain. She is captivated by the beauty of the outside world. On the right is part of an unmade bed, and on the left, a rattan basket containing clothes.”

Painting by S. Sudjojono, Sabda Alam (1961)

Source: OHD Book: Lima Maestro Seni Rupa Modern Indonesia

After seeing the description in the book, Mrs. Rose was quite surprised. How could Oei Hong Djin know such a story? How could he possibly know that she woke up naked? How could Oei Hong Djin know such detailed information? Mrs. Rose also said that she did not remember exactly when she first met Oei Hong Djin; as far as she recalled, she never met Oei Hong Djin while Mr. Djon (Sudjojono) was still alive.

The situation experienced by the families of Soedibio and Sudjojono was similar to that of Hendra Gunawan’s family. The paintings by Hendra Gunawan exhibited in the OHD Museum were very large, measuring 2.5 meters. Some of the paintings displayed include Gemah Ripah Loh Jinawi (1951), Penjual Es Lilin (1970), Berjudi (1975), Pesta Kemenangan (1978), Perayaan 17 Agustus (1980), Penarik Gerobak (1980), Pasar Malam (1981), Perang Buleleng di Bali (1982), and Panen Padi (1980).

Painting by Hendra Gunawan, Penarik Gerobak (1980)

Source: OHD Book: Lima Maestro Seni Rupa Modern Indonesia

Amir Sidharta, a professional auctioneer, also commented that the Hendra Gunawan paintings in the OHD Museum are highly questionable. Amir believes that although the demand for Hendra Gunawan’s paintings is very high, the number of available works is quite limited, making it possible for many forgeries to circulate. Amir also added that large-format works by Hendra are rarely seen on the market, but when Hendra’s paintings boomed in 2005, people started coming forward to offer works, and many were doubtful of their authenticity.

In addition to Amir Sidharta, Astri Wright, a Canadian expert on Hendra Gunawan’s paintings, also commented that she often receives inquiries regarding the authenticity of Hendra’s works from Indonesia, Singapore, the United States, and even Europe — unfortunately, the majority of them are fake. Astri also stated that any Hendra painting purchased after 1988 is most likely a forgery.

Tempo Magazine eventually launched an investigation to find out whether Hendra Gunawan often painted in large formats by locating someone who had guarded Hendra during his imprisonment at Kebon Waru Prison in Bandung from 1965 to 1978. Tempo finally met with a warrant officer named Pak Us, who had watched over Hendra during his time in Kebon Waru Prison.

Pak Us often escorted Hendra out of prison to buy Kuda Terbang-brand paint at a hardware store in the Bandung area. According to Pak Us, Hendra rarely made large paintings because canvas was hard to come by at the time, and Hendra often used burlap sacks as a substitute for canvas. He also said that when Hendra was allowed out of his cell, he would often bring small paintings to trade for sugar, peanuts, and coffee at a shop in the Cikaso area.

According to Pak Us, the only time Hendra ever made a painting larger than 2.5 meters was when he was commissioned to fill the assembly hall of the Military Police on Jalan Jawa. Pak Us didn’t remember the title, but according to a painting dealer in Bandung, the painting was titled Kartosuwiryo, Garuda Troops in Congo, the Lubang Buaya Incident & Trikora in North Kalimantan.

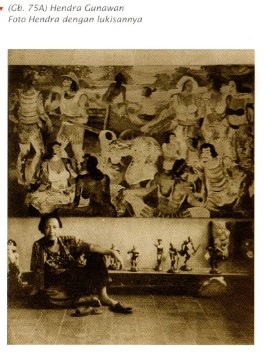

At another time, Hendra Gunawan’s second child from his first wife Karmini carefully observed a photograph in a book published by OHD titled Five Maestros of Modern Indonesian Art. In the book was a photo of his father, wearing a batik shirt and dark trousers, sitting relaxed on a tiled floor. His body rested on his right hand, with his right leg folded inward. His left hand rested on his knee, which was pulled up. A pair of sandals lay in front of him.

Behind him was a row of small statues on a short table attached to the wall, and above it was a large painting (200 x 350 cm) titled Penarik Gerobak (Cart Puller). Hendra’s family was skeptical of the photo because they claimed they had never seen that painting during his time in prison. One of Hendra’s children, named Rosa, said that it should not have been that painting in the photo.

Rosa showed a sepia-colored photo she had in her room to the Tempo editorial team. She claimed the photo was a reproduction of an original she had borrowed from Nuraini, Hendra Gunawan’s second wife and Rosa’s stepmother. Rosa had been visited by two individuals claiming to be emissaries from a major collector in Magelang who were researching Hendra Gunawan. They gave her a list of questions and showed her a photo of Hendra’s grave to convince her. Rosa then lent them several black-and-white photos — all of which were documentation of Hendra’s time in prison.

Photo of Hendra Gunawan (left) is suspected to be a montage, while the photo of Hendra Gunawan (right) is the original photo.

Source: OHD Book: Five Maestros of Modern Indonesian Art & Tempo Issue: 25 Fake Paintings of the Maestro, July 1, 2012

After a long time, the borrowed photos were finally returned, but one photo was missing. The missing photo was the same image of Hendra as the one found in the OHD book, except for one key difference: the background. In the original photo, the painting in the background was Pandawa Dadu. Fortunately, Rosa still had copies of the photos she had lent out, as she had duplicated them back in 1998.

Among the many voices from the artists’ families requesting that their works be removed from the OHD museum, there were also experts, critics, and curators making the same demand. However, Oei did not listen to any of them, remaining firm in his stance that the exhibited collections were authentic—even though he had never consulted the artists’ families nor conducted any laboratory examinations.

What was once a noble mission to introduce the five maestros to the public has suddenly turned into a movement that threatens the future of Indonesian visual art, as it has become a vessel for fake paintings sold by unscrupulous art dealers.

This kind of attitude not only harms the artists’ families but also deceives art enthusiasts who purchase works in the market, damages the credibility of honest art dealers, and disrupts the still-developing ecosystem of the Indonesian art market.