In addition to organizing an exhibition titled “Back to Basic” at his private museum, Oei Hong Djien—commonly known as OHD—also published a book focusing on five major Indonesian artists: Affandi, S. Sudjojono, Hendra Gunawan, H. Widayat, and Soedibio. These five artists were also featured in the exhibition. The book, titled “Five Masters of Modern Indonesian Art: A Paradox,” was intended as a companion to the exhibition and as an informative resource on these legendary painters.

This comprehensive 275-page book contains critical essays on each artist, along with discussions of the works from Oei Hong Djien’s personal collection. For those new to Indonesian art, the book offers valuable insights and serves as an accessible introduction to these iconic figures. It also provides a glimpse into the history and development of Indonesian art during the colonial period and the early years of independence.

Front cover of the book Five Masters of Indonesian Fine Art by Oei Hong Djin

The initial reaction upon learning of the controversy behind this book was one of surprise, given that the publication was intended to serve as an educational resource for the general public seeking to understand the history of Indonesian art. Instead, it has now become a potentially misleading reference. How could Oei Hong Djien risk his reputation as a prominent collector over such a matter?

The book begins with a chapter on Affandi, a renowned painter known for his expressive “squeezing” style—directly applying paint onto the canvas and spreading it with his hands, creating bold and rough strokes. This chapter appears unproblematic, as no objections have been raised by Affandi’s family, and everything seems in order.

However, issues arise in the following chapter, which discusses the works of S. Sudjojono. Several paintings featured in the book have raised concerns, including Perdjuangan Belum Selesai (1967), Pekarangan Rumah (1950), and Sabda Alam (1961).

The painting Perdjuangan Belum Selesai (1967) is particularly problematic. It depicts a figure holding a sickle and another resembling Sudjojono himself holding a hammer—symbols that strongly evoke the emblem of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), which prominently features a hammer and sickle. This association raised significant suspicion, particularly after an interview with Tempo magazine in which Watugunung, one of Sudjojono’s sons, commented, “Father would have to be mad to paint something like that.” According to Watugunung, in 1967 his father was still deeply traumatized by the 1965 G30S tragedy—the mass killing of Communist Party members and sympathizers—and had chosen a period of silence. Sudjojono once told his son, “Nung, a communist must live like a tank. He must know when to move and when to be still.”

Sudjojono’s wife, Rose Pandanwangi, echoed this sentiment, stating with absolute certainty that her husband would never have painted such a work, given his trauma from the anti-communist purge in 1965. By 1967, she explained, he had withdrawn to Jakarta. In addition to the family’s statements, curator Aminudin T.H. Siregar also questioned the painting’s authenticity, citing an inscription that reads “Djokdjakarta, a house in Bantul,” despite the fact that by 1967 Sudjojono had already relocated to Jakarta.

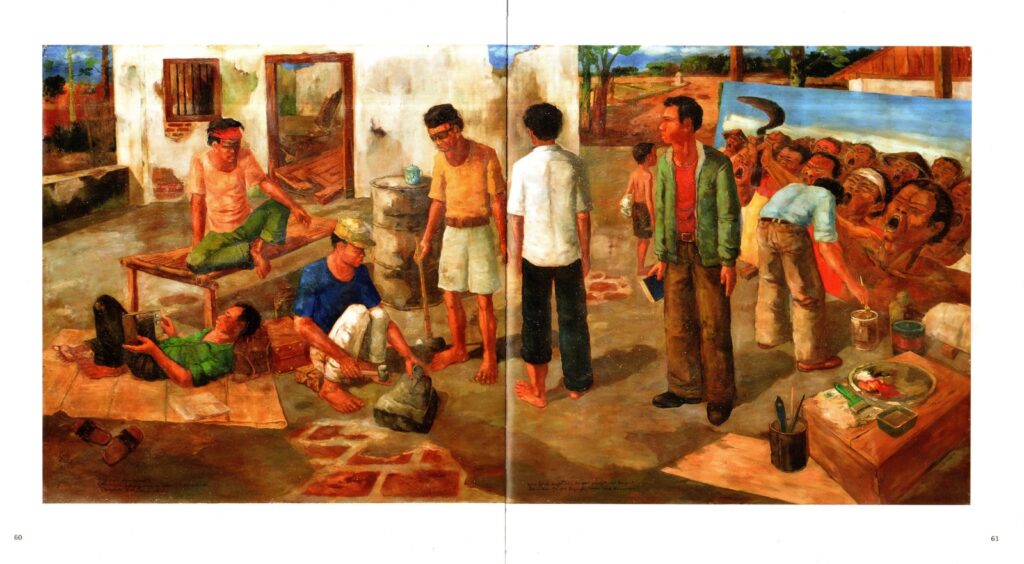

The painting Perdjuangan Belum Selesai (1967) by S. Sudjojono, suspected to be a forgery.

Source: Five Masters of Modern Indonesian Art by Oei Hong Djien.

In the chapter on Hendra Gunawan, initial impressions may not raise any suspicions regarding the artworks featured. However, further scrutiny has led to questions that warrant deeper investigation. The paintings attributed to Hendra Gunawan in this chapter are, on average, quite large—approximately two meters in size. This raises a critical question: “How could Hendra Gunawan have accessed such large canvases while imprisoned in Kebon Waru, Bandung, between 1965 and 1978?” Another question soon follows: “Wasn’t canvas extremely scarce during that period, to the point that many artists resorted to using burlap sacks as substitutes?”

An article published by Tempo sought to answer these questions through research and interviews, including with a prison guard who had directly overseen Hendra Gunawan during his incarceration—a man named Pak Us. In the interview, Pak Us stated, “Hendra rarely painted large works. Canvas was hard to come by at the time. Hendra often painted using burlap sacks.”

Pak Us added that, to his recollection, the only time Hendra worked on a large-scale painting was when the Military Police requested him to produce a work to decorate their main hall. That particular painting measured around 2.5 meters. This account was further corroborated by Hendra Gunawan’s wife, Nuraini, who confirmed that she had assisted her husband in creating the piece while he was imprisoned.

In 1980, Hendra Gunawan moved to Bali, already in poor health at the time—so much so that he reportedly did not recognize one of his major collectors, Mr. Ciputra, who had previously acquired a large number of his paintings. While living in Bali, Hendra once used 20 of his paintings as collateral at a bank simply to survive. Later, Mr. Ciputra redeemed and purchased all of those works. According to Nuraini, Hendra’s wife, she could not recall anyone else besides Mr. Ciputra acquiring Hendra’s works during that time, although it is possible that one or two paintings ended up in other hands.

Hendra Gunawan’s large-scale paintings are known to be held in two locations: by the Ciputra collection and at the Mahudara Mandara Giri Bhuvana Museum in Bali. Among those in the Ciputra collection are Pangeran Diponegoro Terluka and Ali Sadikin, while Perang Buleleng (measuring 400 x 200 cm) and Trunyan (200 x 260 cm) are held by the Mahudara Mandara Giri Bhuvana Museum.

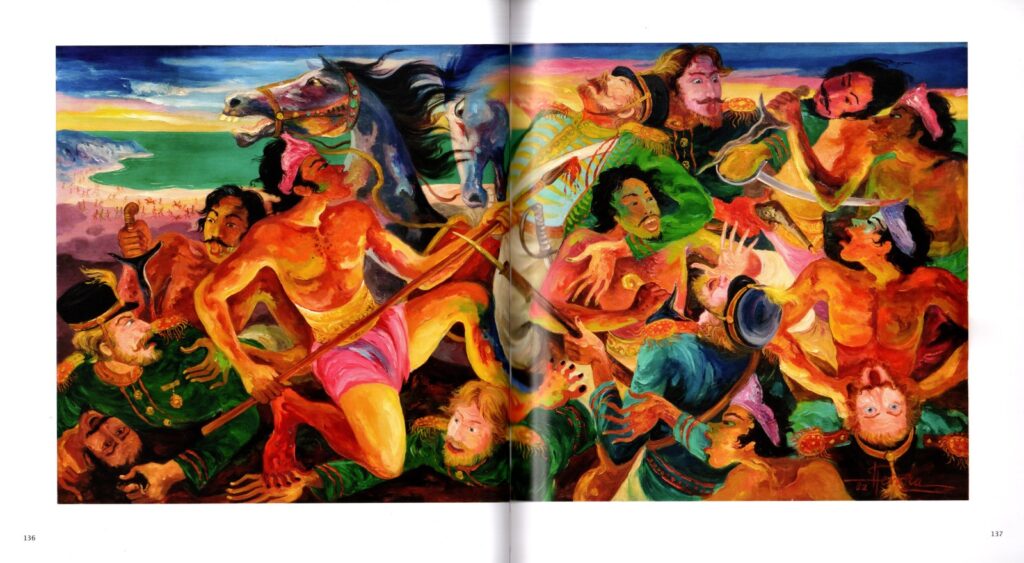

Here is where the discrepancy arises: in the book, OHD also features a painting titled Perang Buleleng, but with different dimensions—150 x 300 cm. The Mahudara Museum has confirmed that the version they hold is the original.

The painting Perang Buleleng (top) owned by Oei Hong Djien measures 150 x 300 cm, while the painting Perang Buleleng (bottom) belongs to the Mahudara Mandara Giri Bhuvana Museum in Bali. Sources: Five Masters of Modern Indonesian Art by Oei Hong Djien & Tempo Magazine, July 1, 2012 edition.

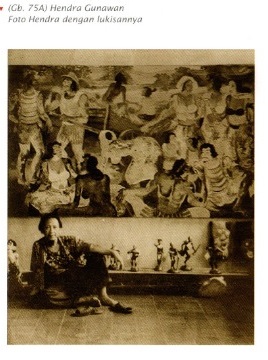

The oddities do not stop there. Another peculiar detail was pointed out by Hendra Gunawan’s daughter, Rosa. It concerns a photograph of Hendra Gunawan seated, with the painting Penarik Gerobak (Cart Puller) in the background. Rosa was surprised upon seeing the image, as it closely resembled a photo in her personal collection — but with a different background.

Previously, two individuals had visited Rosa, claiming to be representatives of a prominent collector from Magelang conducting research on Hendra Gunawan. They showed her a photograph of Hendra Gunawan’s grave, and because they appeared trustworthy, Rosa agreed to lend them several archival photographs of Hendra Gunawan from his time in prison. However, one of those photos — the one now appearing in the book — was never returned.

According to Rosa, the original photograph should have featured the painting Pandawa Dadu (Pandawa Playing Dice) in the background, not Penarik Gerobak.

Photograph of Hendra Gunawan with the painting Penarik Gerobak (left) from OHD’s book, and a photograph of Hendra Gunawan with the painting Pandawa Dadu in the background, owned by Hendra Gunawan’s daughter (right). Source: Five Masters of Modern Indonesian Art book & Tempo Magazine, July 1, 2012 edition.

After uncovering various anomalies, this book instantly became a perplexing paradox. On one hand, it may serve as a valuable resource for those wishing to learn about the history of Indonesian fine art; on the other hand, it also risks undermining that very history.